We use the word “love” to describe our feelings for pizza, our parents, and our partners. It is a linguistic catch-all that often fails to capture the complexity of our actual experiences. Is the quiet comfort of a 30-year marriage the same emotion as the electric anxiety of a new crush? If not, how do we categorize the difference?

Psychologists and neuroscientists have spent decades attempting to map this terrain, moving beyond poetry to define the specific cognitive and biological architectures that underpin our deepest bonds. What they have found often contradicts our most held cultural assumptions, particularly regarding the stability of companionate love.

This article breaks down five surprising takeaways from the scientific classification of love that might change how you view your own relationships.

Is Companionate Love More Stable Than Passionate Love?

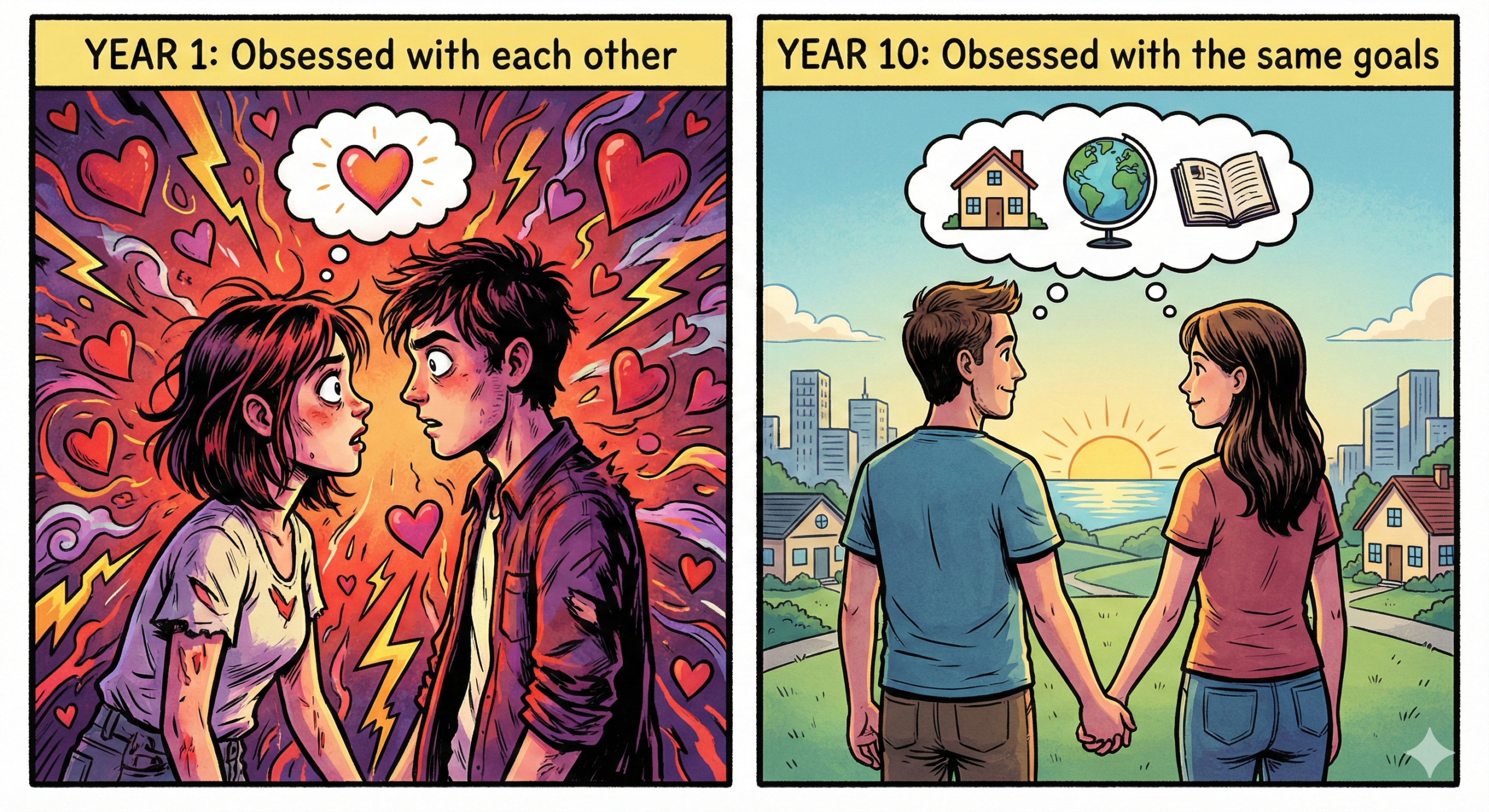

Yes, scientific research confirms that companionate love is significantly more stable than passionate love. While passionate love is driven by dopamine and usually lasts only 12 to 18 months, companionate love is built on oxytocin and vasopressin. This biochemical shift moves the relationship from volatile obsession to a “sturdy evergreen” state characterized by deep security, trust, and shared life goals, which are the foundations of long-term stability.

| Feature | Passionate Love | Companionate Love |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Dopamine (The “High”) | Oxytocin & Vasopressin (Bonding) |

| Duration | Temporary (12–18 months) | Long-term (Decades) |

| Dominant Feeling | Thrill, Anxiety, Obsession | Calm, Security, Comfort |

| Main Danger | Fades quickly, feeling like “loss” | Can feel “boring” without effort |

| Success Metric | Intensity of emotion | Quality of friendship |

1. The 33 Dimensions of Companionate Love vs. Passionate Love

We tend to think of love as a binary state: you are either in it, or you aren’t. However, modern psychometrics suggests love is far more granular. Researchers using the Multidimensional Love Scale (MLS) have identified at least 33 distinct dimensions that comprise our romantic feelings.

These dimensions range from “Yearning” and “Irrationality” to “Companionship” and “Practicality.” While these dimensions cluster into two main types—Passionate Love (intense longing) and Companionate Love (deep attachment)—they share the exact same building blocks, just mixed at different levels.

If you feel a shift in your relationship, it may not be that love is “gone,” but rather that the volume knobs on specific dimensions—like “Obsession” or “Idealization”—have been turned down, while others like “Trust” or “Communion” have been turned up.

2. The Evergreen Myth: Why Companionate Love Declines Over Time

For decades, the prevailing wisdom in relationship psychology was that while Passionate Love burns out quickly (a “fragile flower”), Companionate Love is resilient and grows over time. Early researchers famously hypothesized:

“Passionate love is a fragile flower—it wilts in time. Companionate love is a sturdy evergreen; it thrives with contact.”

However, empirical data has challenged this comforting narrative. When researchers interviewed newlywed couples and then followed up a year later, they found that time had a “corrosive” effect on both types of love. Contrary to the expectation that companionate love would remain stable or increase as the “honeymoon” phase ended, it declined in parallel with passion.

This reveals a critical truth: there is no “autopilot” phase of love. The assumption that friendship and attachment will naturally deepen without effort is a myth. Both the fire of passion and the structure of companionship require active maintenance to survive the erosion of time.

3. Neuroscience of Companionate Love: How the Brain Sustains Long-Term Bonds

We are often told that the intense, dopamine-fueled “spark” of romance has an expiration date, typically between 6 to 30 months. However, neuroimaging studies (fMRI) have revealed a fascinating subgroup of long-term couples—married an average of 21 years—who claim to still be “madly in love.”

When these individuals viewed photos of their partners, their brains showed activation in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the same dopamine-rich reward system active in new lovers. The key difference? The long-term lovers did not show activation in the brain regions associated with anxiety and obsession that plague new relationships.

This suggests that it is biologically possible to maintain the “reward” and motivation of romantic love for decades without the stress of early infatuation. Long-term passion isn’t an oxymoron; it’s a distinct neural state characterized by high reward and high calm.

4. Cultural Expressions of Companionate Love: Acts of Service vs. Verbal Affirmation

The architecture of love is not just biological; it is deeply cultural. In Individualistic cultures (like the U.S.), love is often explicit, verbal, and centered on self-expression (“Words of Affirmation”). In Collectivist cultures, companionate love is often implicit and communicated through Acts of Service and contextual care.

A poignant example of this is the “cut fruit” phenomenon observed in many Asian families. A parent or partner may never verbally articulate “I love you,” but the act of silently delivering a bowl of peeled, cut fruit serves as a powerful, non-verbal declaration of care and matrimonial love.

We often misdiagnose relationships as “loveless” simply because we are listening for the wrong language. Understanding that love can be encoded in duty and service rather than verbal praise is essential for navigating cross-cultural or diverse relationship dynamics.

5. The Self-Expansion Model: Overcoming Boredom in Companionate Relationships

Why does love feel so exhilarating in the beginning and often boring later? The Self-Expansion Model offers a cognitive explanation. It posits that humans have a fundamental motivation to expand their potential efficacy—to do more and be more.

When we fall in love, we rapidly “include the other in the self,” acquiring the partner’s resources, perspectives, and identity as our own. This rapid expansion creates a rush of positive affect. However, once we know a partner well, this expansion naturally slows down, leading to the “rustiness phenomenon” or boredom commonly associated with long-term companionate love.

To keep love alive, you don’t just need “date nights”; you need novelty. Engaging in exciting, new activities together reactivates the self-expansion process, mimicking the rapid growth of early love and literally re-wiring the brain to associate the partner with reward.

Summary:

Love is not a magical force that exists outside of us; it is a constructed experience built on neurochemistry, cultural scripts, and daily behaviors. It is comprised of dozens of dimensions, susceptible to the erosion of time, and reliant on our continued willingness to grow.

As you reflect on your own relationships, consider this: Are you waiting for the architecture of your love to sustain itself, or are you actively drafting the blueprints for its next expansion?

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is companionate love more stable than passionate love?

Companionate love is built on the steady release of oxytocin and vasopressin, which promote bonding and security. Unlike the dopamine-heavy “high” of passionate love, these chemicals don’t drop off as quickly, providing a more resilient emotional foundation for long-term partners.

How long does passionate love typically last?

Most psychological research suggests the “honeymoon phase” of passionate love lasts between 12 to 18 months. After this, the brain’s reward system stabilizes, and the relationship naturally transitions into a companionate phase.

Can you have both types of love at once?

Yes. fMRI scans of “long-term lovers” show that it is possible to maintain the dopamine-driven reward of passion alongside the oxytocin-driven security of companionate love, especially when couples engage in new, challenging activities together.

Research Sources

- Karandashev, V., & Clapp, S. (2016). Psychometric Properties and Structures of Passionate and Companionate Love. Interpersona, 10(1), 78-92. https://interpersona.psychopen.eu/index.php/interpersona/article/view/3473

- Hatfield, E., Pillemer, J. T., O’Brien, M. U., & Le, Y. L. (2008). The Endurance of Love: Passionate and Companionate Love in Newlywed and Long-Term Marriages. Interpersona, 2(1), 35-64. https://interpersona.psychopen.eu/index.php/interpersona/article/view/3177

- Acevedo, B. P., Aron, A., Fisher, H. E., & Brown, L. L. (2012). Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(2), 145-159. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21208991/

- Hubbard, C. (2023). Love Culture. Rhetorikos. https://rhetorikos.blog.fordham.edu/?p=1885

- Cherry, K. (2025). Passionate Love vs. Compassionate Love: What’s the Difference?. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/compassionate-and-passionate-love-2795338

- Xu, X., Lewandowski Jr, G. W., & Aron, A. (2019). The Self-Expansion Model and Relationship Maintenance. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/relationship-maintenance/selfexpansion-model-and-relationship-maintenance/6B38610862E50CB30312F5D250099F68

About DailyCheatSheet: We distill complex research into actionable insights. Our team spends 10+ hours researching each topic to bring you science-backed mental health and personal development content. Have feedback? Contact us.